Climate and Growing Season Precipitation

Introduction

Like temperature, precipitation in the Rufiji Basin closely correlates with elevation. The higher elevation areas receive over 1,000 mm per growing (rainy) season from December to May, whereas the lower elevation areas can receive less than 500 mm per season.

Rice is demanding of water, requiring substantially more than other grain crops grown in Tanzania. Although it does not require continuously saturated soil, it grows poorly if water stressed particularly during the transplanting and reproductive stages. Much of the rice grown in the Rufiji Basin is under rainfed conditions with minimal irrigation, so precipitation amounts and timing are important. Depending on the variety, it can require between 450 and 700 mm during its growing season, or between 900 to 2,250 mm/day.

Water requirements for maize vary greatly depending on variety, soil type and temperature, but generally it does best between 500 to 800 mm/growing season. However, yields are very sensitive to water deficits during the flowering period. Severe water deficits during silking and pollination may lead to little or no yield. Farmers have noticed an increase in the length and frequency of dry spells in the season, and this could threaten yields. Other changes in precipitation, particularly in growing season onset and length, are also affecting successful planting, growth and yield.

Current

The current distribution of precipitation leads to a highly varied agricultural landscape. In the lowlands, the combination of warm temperatures and lower precipitation leads to shorter growing seasons, water deficits and lowers crop yield, especially without supplemental irrigation. The Highlands, in contrast, are well watered and cool. They have longer growing seasons and the crops have less water stress.

Farmers have noticed that the onset of the rainy season is less reliable, and that dry spells during the rainy season have become more common. These trends in precipitation, particularly the erratic onset of the growing season and possibly shorter rainy seasons, would affect successful planting, growth and yield.

Future - 2050

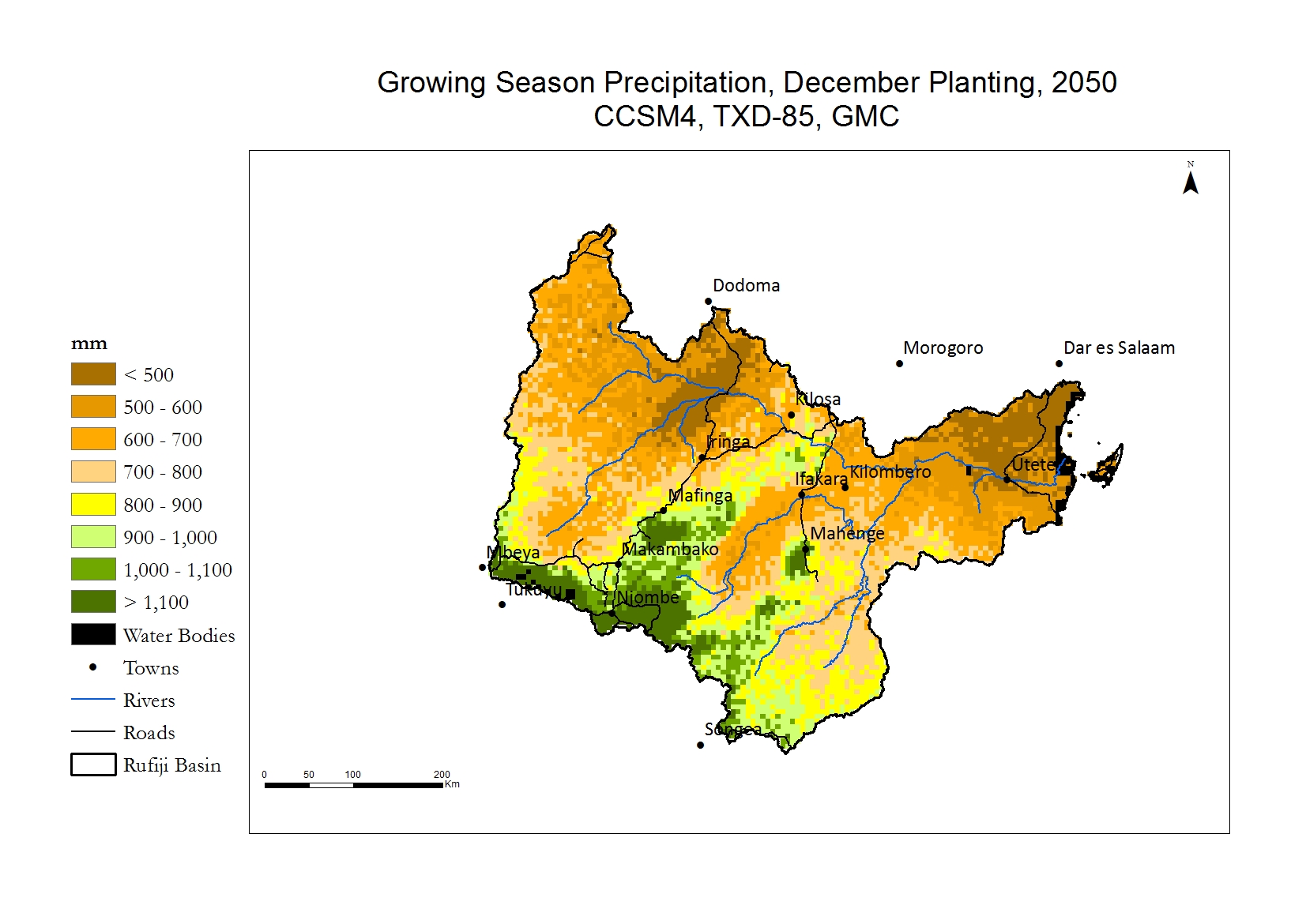

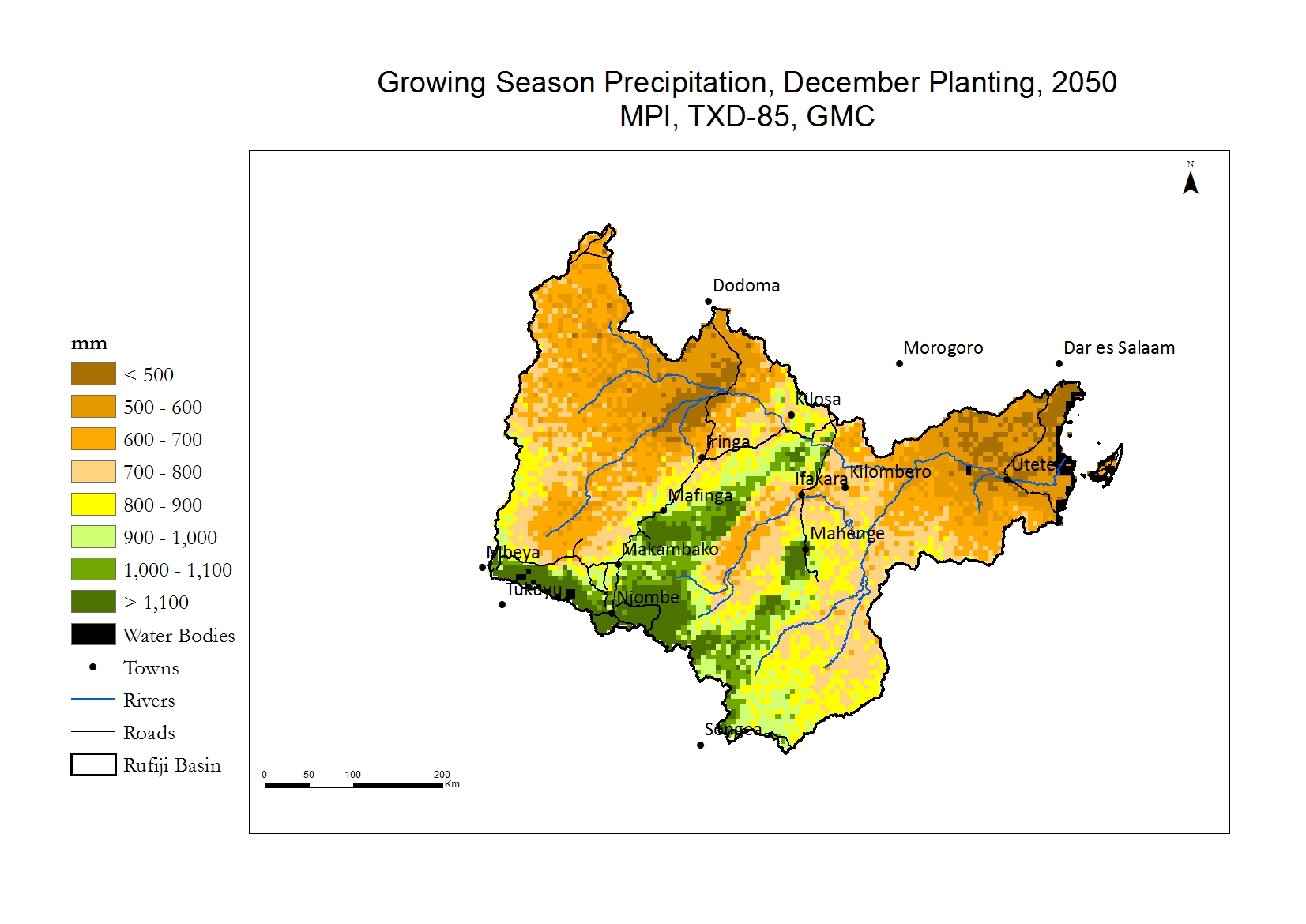

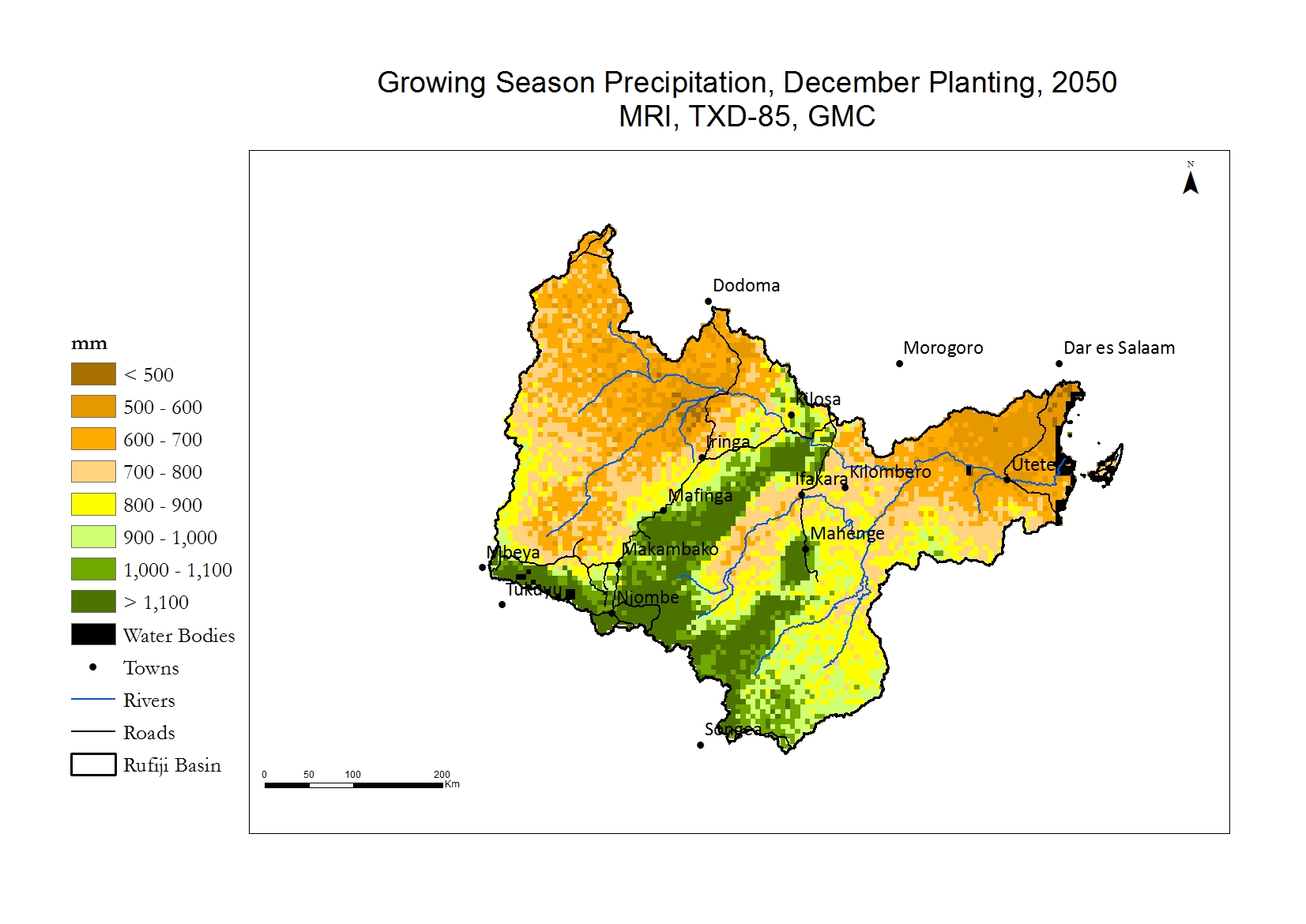

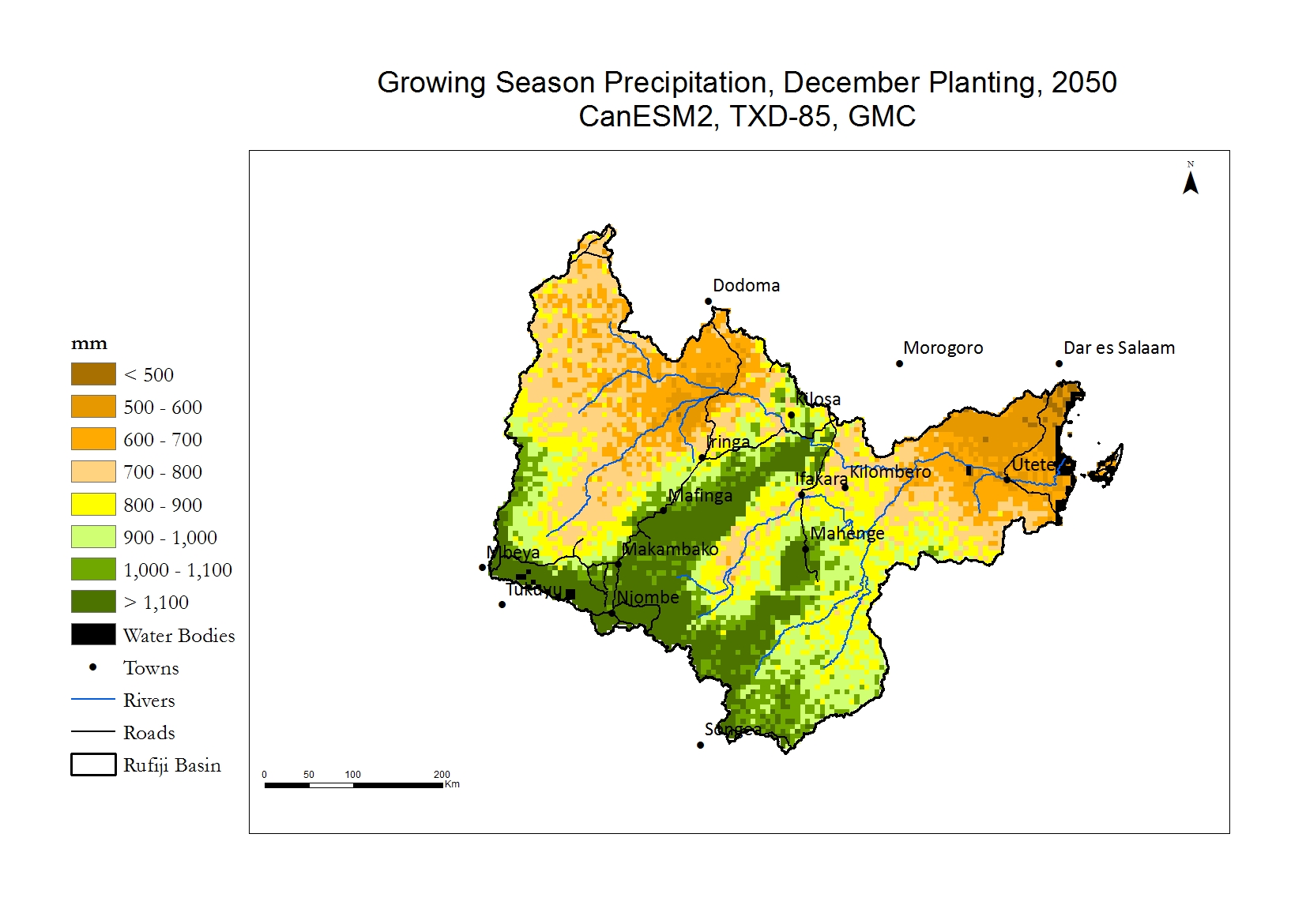

The four GCMs all indicate that the general pattern of well-water Highlands and drier lowlands is expected to continue. The models differ somewhat in the quantity of precipitation that is expected during the growing season. Please note that the future climate projections are not certain and take the results as representative trends.

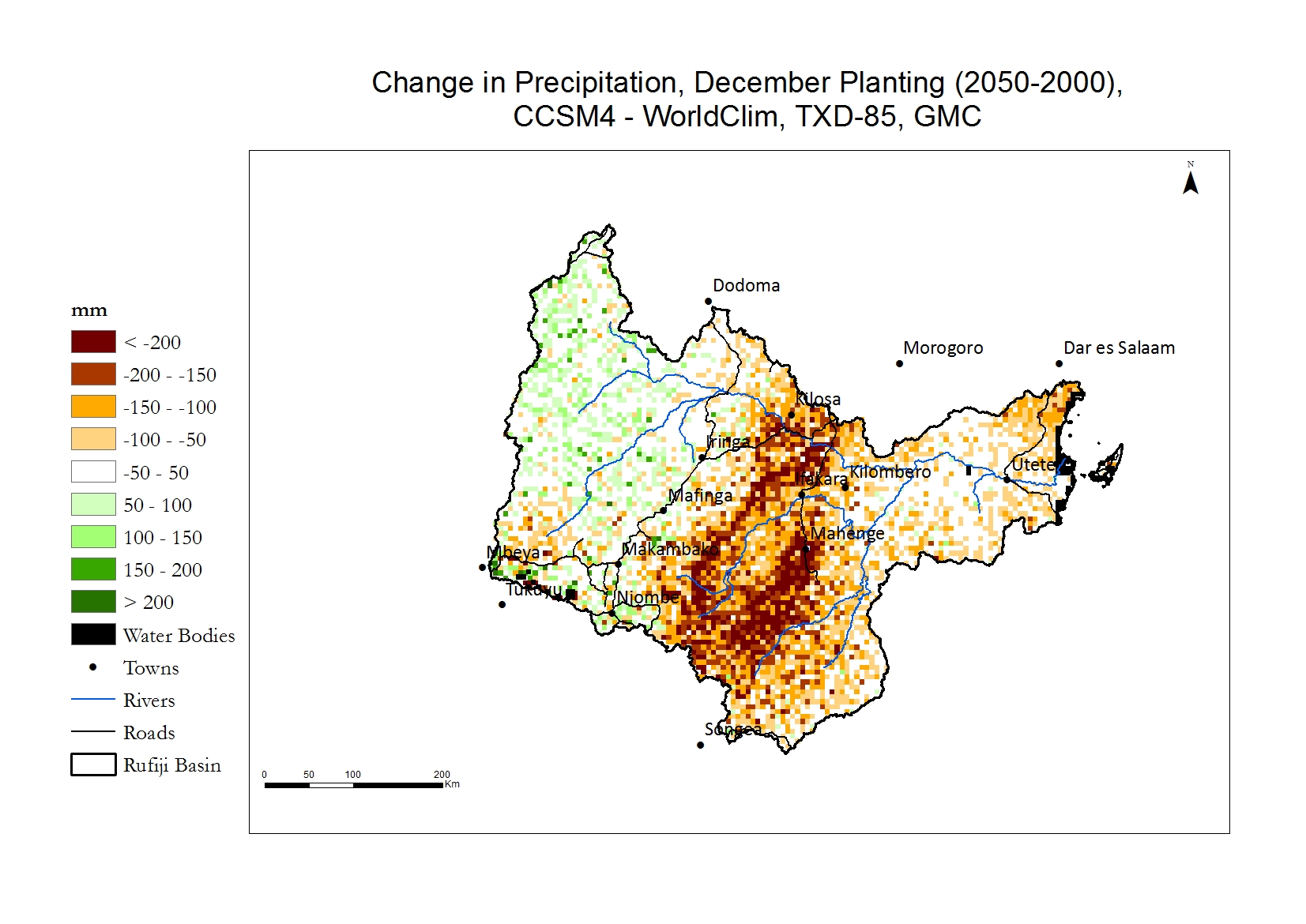

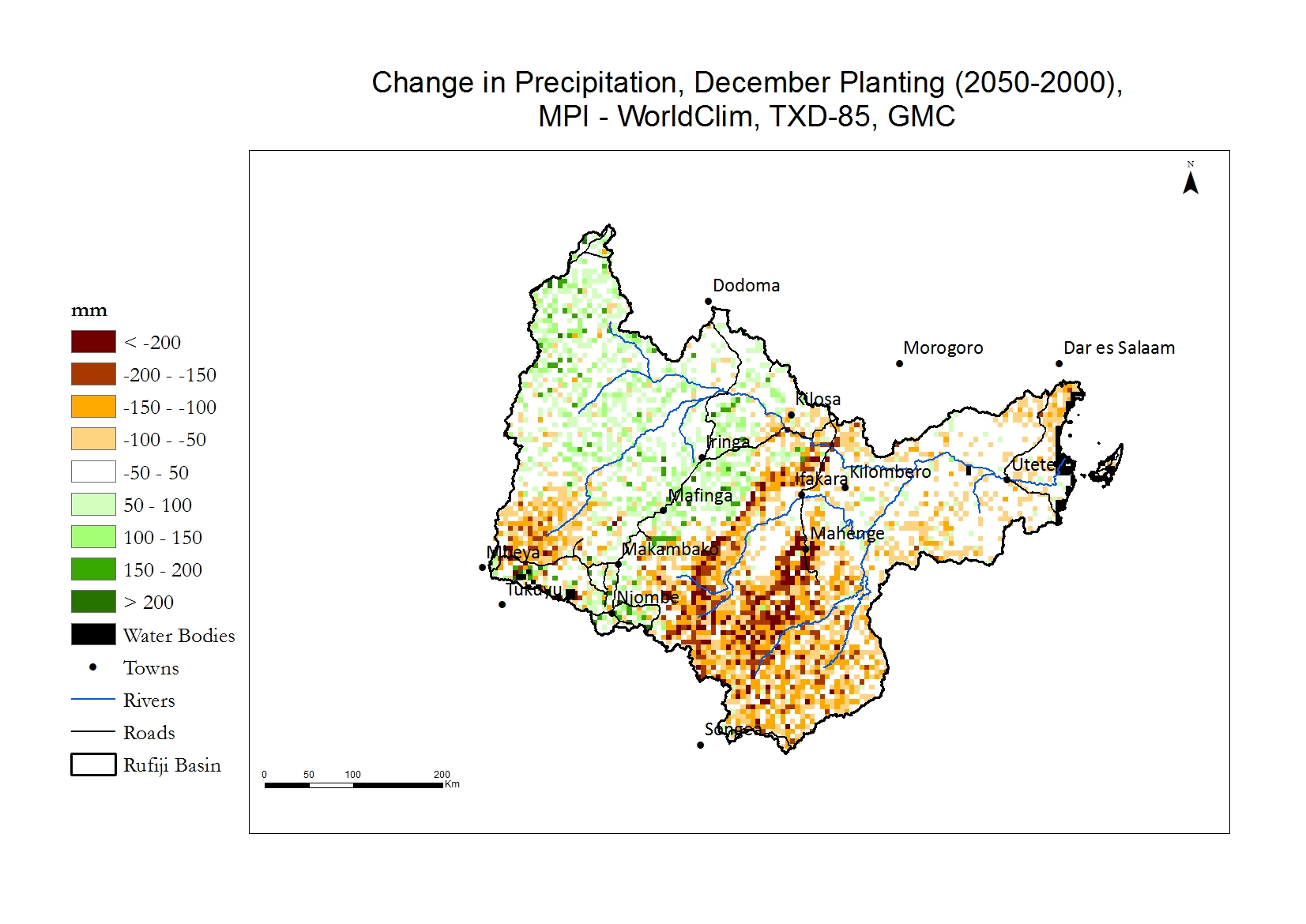

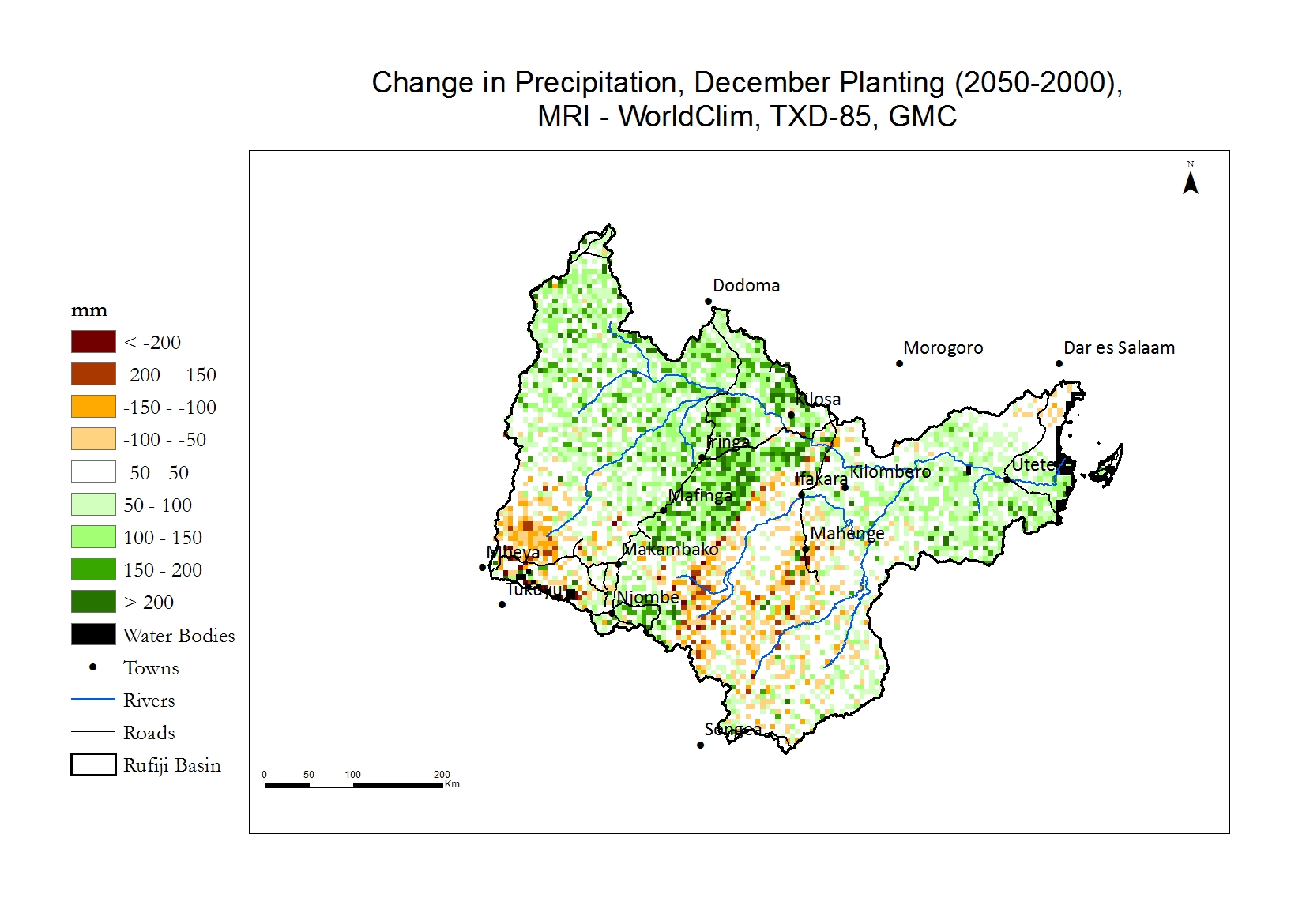

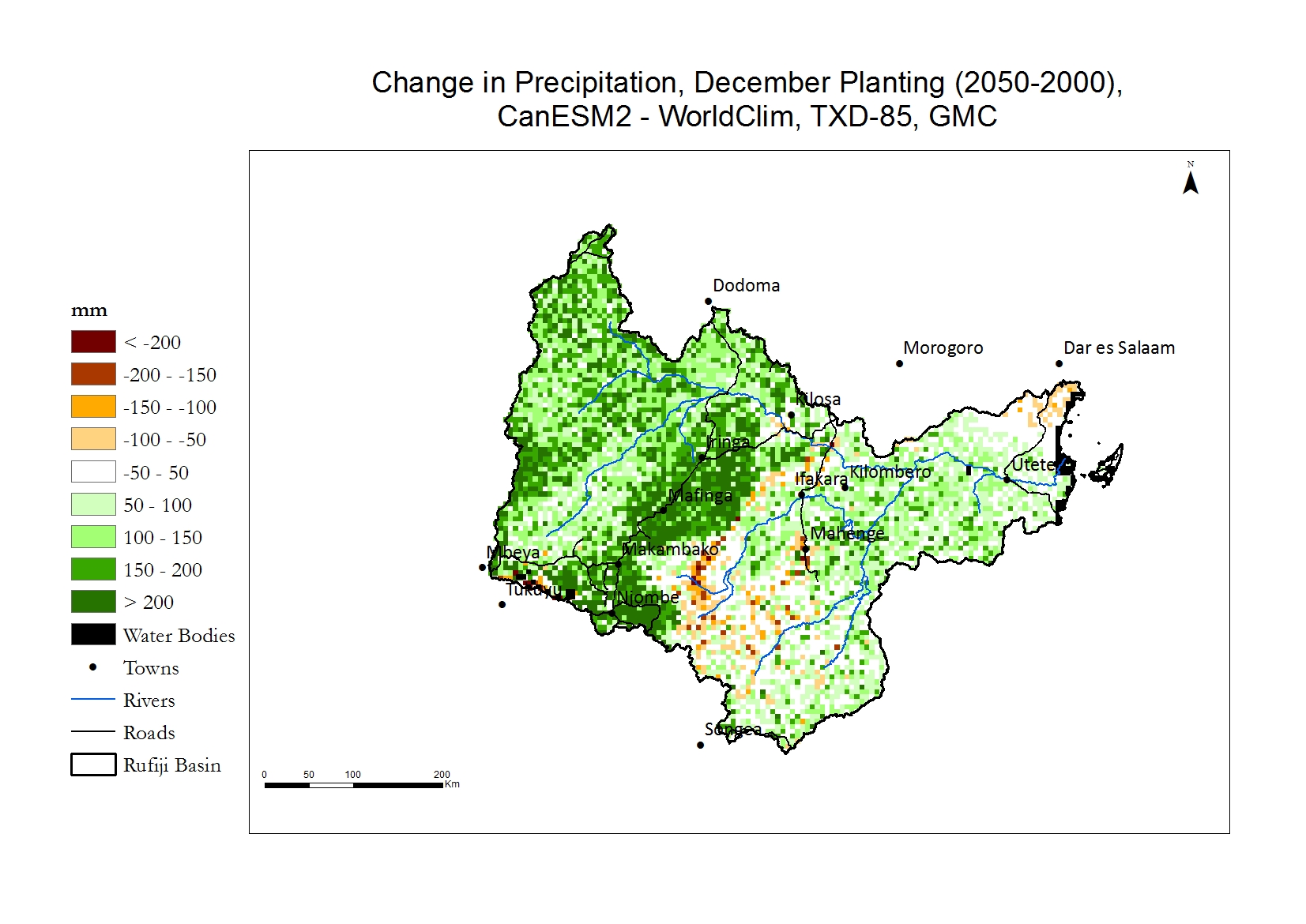

Change

These maps indicate the change in millimetres (mm) of precipitation falling during the growing season from 2000 to 2050. The green color indicates an increase, white no or little change, and brown a decrease in precipitation. However, the actual amount of change is relatively small, between +200 and -200 mm per growing season.

The GCMs differ somewhat in their projections of change. All GCMs, especially CCSM4, indicate that the Highlands will receive somewhat less precipitation in the future, but will remain well watered. The GCMs differ, however, in whether and how much additional precipitation will fall in the lowlands, particularly west of the Iringa Highlands. CCSM4 is again the driest model indicating very little if any additional precipitation, and CanESM2 is the wettest projecting increases of over 200 mm per growing season.

Comparison

Moving the slider provides insight into where precipitation is projected to change, according to each of the four GCMs. Again, WorldClim represents precipitation in 2000, and maps with the name of the GCM are for 2050. The change in precipitation between 2000 and 2050 is projected to be small, compared to the wide differences across the Basin.

The impact of climate change on crops in the Basin is not necessarily changes in the amount of total growing season precipitation, but alterations in the distribution of precipitation during the season, and changes in the onset and cessation of the rainy season.

Current

Current

Current

Current

Current

Current

Current

Current